Inside the Tiny Shed of a DIY Miniature Maker in Scotland

Karen Bones doesn’t just recreate buildings — she rebuilds memory, character, and a bit of grit, brick by brick. From Glasgow pubs to the cottages of Culross, her miniatures are full of love, imperfection, and life.

We’re in the shed now.

It’s tiny and cosy, packed with cardboard buildings, glue pots, paints, music, stained glass — and a little doll that looks suspiciously like the artist herself.

This is where Karen Bones builds her world — one miniature at a time.

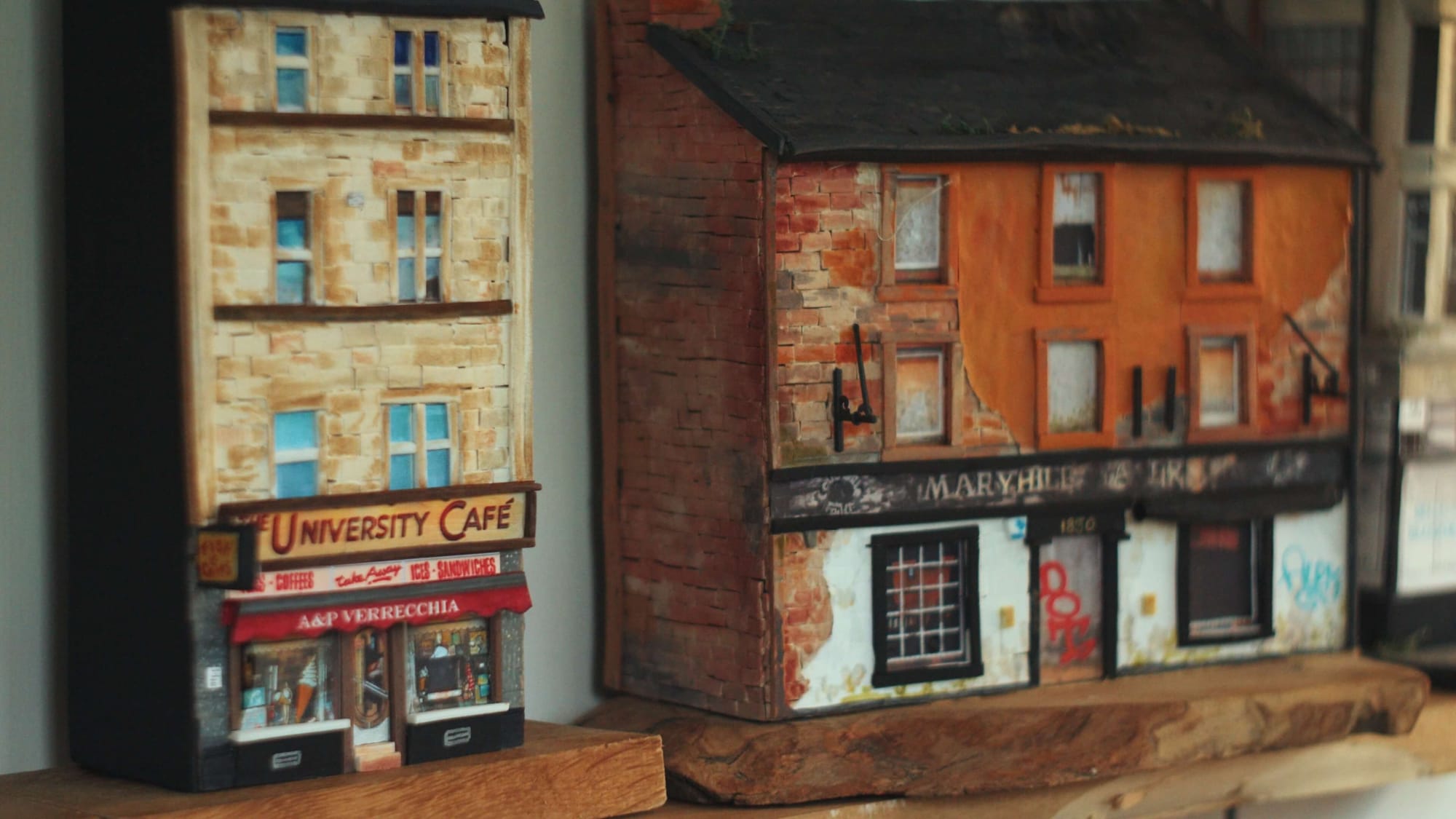

A former painter and lifelong goth, Karen now spends most days turning cardboard into buildings. Not grand ones or architecturally precise models — but the places that feel real. The pubs with nicked tiles, the houses with ghost signs, the lanes that smell like a night well spent.

She doesn’t work from blueprints. She works from memory and impressions. A flicker of light on stained brick. A story someone tells at a market. A place that just won’t let her walk past.

Her models aren’t replicas.

They’re portraits — full of warmth and weathering. And Karen loves every minute of making them.

In Their Own Words: Karen on Finding Her Way into Model Making

Full transcript of our conversation with Karen.

My name is Karen, and I make miniature models. Before that, I worked as a freelance illustrator for years, mostly sketching buildings in Culross and Fife. But before illustration, I worked in the bar trade. Drawing bars came naturally, and everything really began there.

I studied illustration and printmaking at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee. Later, I discovered an artist in London building models from balsa wood and card. I wondered if I could do something similar using recycled cardboard. I had loads of it lying around the studio.

My first model was very rudimentary, very basic, but it was surprisingly well received. Since then, it’s taken off. I now work mainly with recycled cardboard, though I use anything that fits — buttons, packaging, plastic. But it always comes back to cardboard.

Iconic Builds

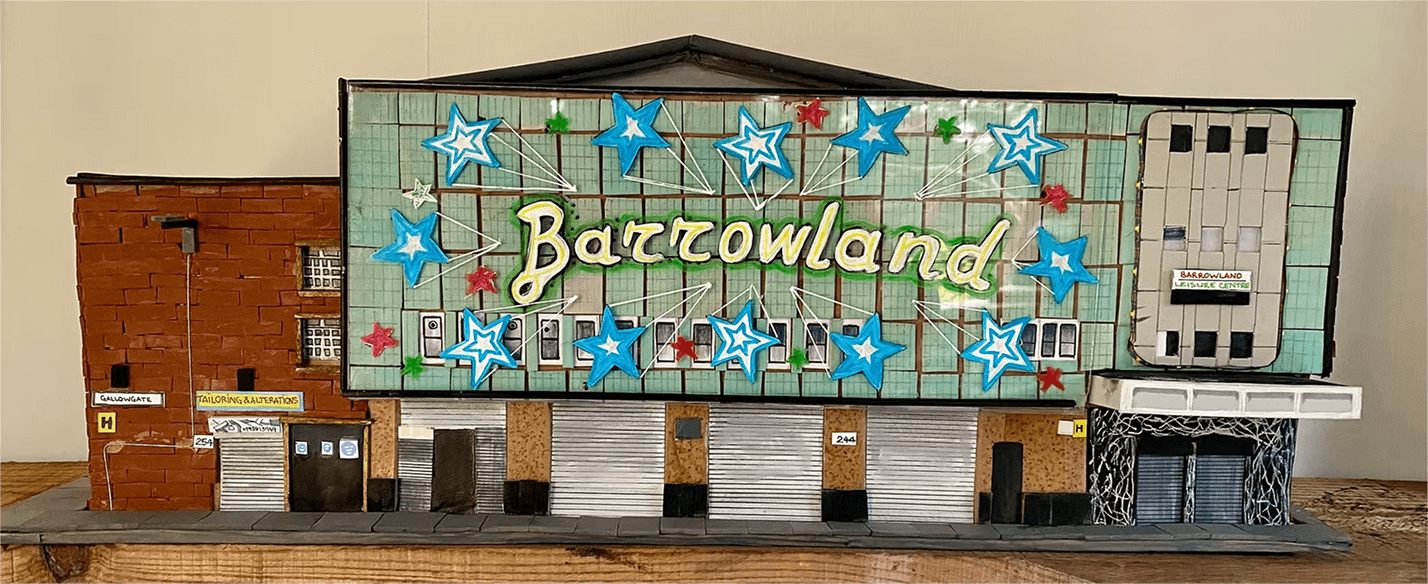

My years working in Glasgow’s bar and music scene have shaped my work. Bars and venues are a recurring theme. Many are now closing, which makes documenting them feel even more urgent. Each model becomes a kind of memory-keeper.

My favourite model so far is probably Glasgow Barrowland. It was the first one I lit from the inside, which made it a real challenge — but it’s also the one I’m best known for now. My favourites change often, though. I’m always drawn to whatever catches my eye at the moment.

“Nick’s Cave”

I build everything in my wee shed. It’s a small 8×6 sanctuary in the garden that I retreat to constantly, shut the door, music on, fire on, and get building. It was bought during lockdown when my husband took over the spare room. I insulated and decorated it myself. It’s cosy and full of everything I need.

My shed has become a personal space full of little talismans. I’m a huge Nick Cave fan, so a friend dubbed it “Nick’s Cave.” I listen to his music as I work. I also have stained glass from a friend, and a photo of five of my oldest college friends right above my desk.

I have lots of things around my shed that are really personal to me. Apart from the posters and postcards of Nick Cave, right in front of where I work, there’s a photograph of five of my oldest college friends — they inspire me and help keep me going. I also have quite a bit of stained glass in the shed, made by a friend of mine. I just love looking at it with the light shining through — it brings me a lot of joy.

I also have a doll in my shed that, mysteriously, looks just like me. She’s a fairly new addition and came from a girl I spoke to online after seeing her work on Facebook — she makes dolls and teddies. She doesn’t usually take commissions, but I used to make puppets myself when I was at art college — I’ve gone from figurative work to buildings since then. When I saw her dolls, I asked if she’d be up for making one of me. I’d never done one of myself, and I thought — why not?

I wanted it to look like me in the ’90s. I’m still a goth, but these days I’m more of an ageing goth. She was lovely and put it together with all the right touches — stripy tights, leopard print — and sent it over. I absolutely love it. The doll now sits on a shelf in my shed and watches me while I work.